|

|

|

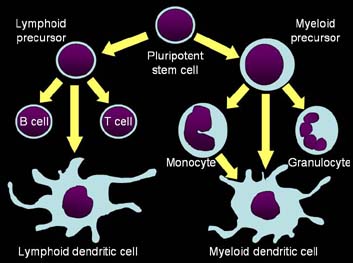

Figure 1. Schematic

indicating the proposed lineage of Langerhans cell

development from myeloid, monocytic, and lymphoid precursor

cells.

|

Incidence

Cancer is one of the

major causes of death in dogs.3, 7 There is a large amount

of clinical information regarding clinical signs, diagnosis, and

treatment of canine neoplasia; however, relatively little information

exists on the incidence of many types of cancer in this species. It is

well accepted that cutaneous neoplasms are among the most commonly

observed forms of cancer in dogs. Furthermore, cutaneous histiocytoma

has been reported to be the most common presentation of cutaneous

neoplasia, and the most commonly observed form of cancer overall.6,7

Signalment

Canine cutaneous

histiocytoma is most commonly observed in young dogs and tumor

incidence drops precipitously after three years of age. While this

tumor is most commonly observed in young dogs, most studies indicate

that it is infrequently observed in older animals. Breeds at risk

include Flatcoat Retrievers, English Bulldogs, Scottish Terriers,

Greyhounds, Boxers, and Boston Terriers.

Gross Lesions

Cutaneous histiocytomas

are generally observed by the practitioner as solitary, red,

dome-shaped, sparsely haired nodules that appear rapidly (Fig. 2).

They often are ulcerated, but are non-painful. The most common sites

of tumor development include the head, pinna, and neck, especially in

young dogs.3 More rarely, neoplasms may occur on the trunk

and extremities, and frequently involve the feet and toes of older

individuals (KSL, personal observation). Rarely, histiocytomas may

arise in multiple sites.

The metastatic

potential of histiocytomas has not been studied directly, but reports

of tumor metastasis are rare. Death due to cutaneous histiocytoma has

not been reported. It is generally accepted that this tumor does not

readily metastasize, and should be considered benign.

|

|

| Figure 2.

Histiocytomas of the pinna (left) and foot (right) appear as

red, raised, sparsely haired masses (Courtesy of Noah's Arkive,

University of Georgia). |

Diagnosis

Cutaneous histiocytomas

may be readily diagnosed using a combination of clinical signs,

signalment, and fine-needle aspiration cytology. Rarely, a

histopathologic diagnosis may be required. In biopsy sections,

histiocytomas are circumscribed, nonencapsulated dermal masses

composed of sheets of round cells. Individual cells have a round to

reniform nucleus with occasional nucleoli and moderate amounts of

cytoplasm(Fig. 3). Increased mitoses, discrete necrosis, and

infiltrates of small lymphocytes may be observed. Infrequently,

cutaneous histiocytoma may be confused histologically with

granulomatous inflammation, poorly granulated mast cell tumors,

plasmacytomas, and cutaneous lymphosarcoma.2

|

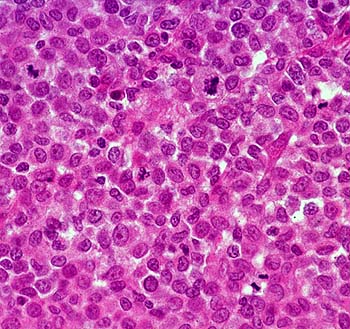

| Figure 3.

Biopsy specimen of a histiocytoma composed of sheets of round

cells. Scattered mitoses are present (Hematoxylin and eosin

stain, courtesy of Noah's Arkive, University of Georgia). |

Cytology

The various round cell tumors of dogs

have distinct cytologic characteristics that are presented in Table 1.

Additional information can be found in clerkship papers Canine

Round Cell Tumors and Mast

Cell Disease in Dogs and Cats: An Overview.

Table 1.

Cytologic features of round cell neoplasms of dogs.

| Feature |

Mast Cell Tumor |

Cutaneous Histiocytoma |

Transmissible Venereal Tumor |

Plasmacytoma |

Cutaneous Lymphoma |

| Nucleus |

Often obscured by purple granules |

Eccentric and oval to cleaved (butt cells) |

Round

Cordlike chromatin

Single nucleolus

|

Eccentric and round to oval

Binucleate and trinucleate cells

Anisokaryosis may be marked

|

Round to slightly indented nucleus

Finely stippled chromatin

|

| Nucleolus |

Not seen unless cells poorly granulated |

Inconspicuous and small nucleoli |

Single prominent, blue nucleolus |

Occasionally to infrequently observed |

Multiple nucleoli |

| Cytoplasm |

Numerous purple granules |

Abundant, pale blue, non-vacuolated cytoplasm |

Moderate to abundant, pale blue cytoplasm with distinct

vacuoles |

Moderate amount of medium to dark blue cytoplasm

Perinuclear clearing or Golgi zone

|

Small rim of dark blue, granular cytoplasm

Occasional cytoplasmic fragments seen

|

| Other Characteristics |

Granules may stain poorly with Diff Quik stain

Eosinophils may be present

|

Usually single ulcerated mass

Lymphoid infiltrates may be present

|

Mitoses may be abundant

Secondary inflammation may be present

|

Typical plasma cells may be observed |

Multiple neoplasms usually present |

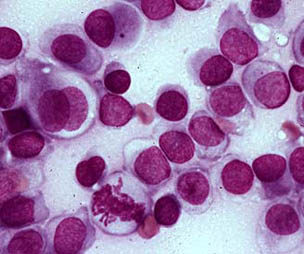

The fine-needle

cytologic characteristics of canine cutaneous histiocytoma have been

well described and usually are diagnostic (Fig. 4).6

Histiocytoma cells have an eccentric, oval to reniform nucleus with

occasional nuclear clefts. The chromatin pattern is finely granular

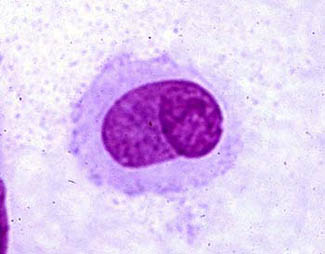

and nucleoli are inconspicuous. Cells that contain nuclear clefts are

sometimes referred to as "butt cells" because of their

characteristic morphology (Fig. 5). The cytoplasm is abundant, lightly

basophilic, and lacks vacuoles or granules.

|

|

| Figure 4. Fine-needle aspirate

of a histiocytoma containing cells with a round to oval

nucleus and moderately abundant blue cytoplasm that lacks

vacuoles and granules. A binucleated cell and mitotic figure

are present (Wright stain, courtesy of Noah's Arkive,

University of Georgia). |

Figure 5. Histiocytoma cell

with a nuclear cleft and typical butt cell morphology. |

Treatment and

Prognosis

| Note: Treatment of animals should only be

performed by a licensed veterinarian. Veterinarians should

consult the current literature and current pharmacological

formularies before initiating any treatment protocol. |

Most cutaneous

histiocytomas regress spontaneously regardless of the course of

treatment pursued.6, 9 Regression of the tumor has been

correlated with infiltration of T- lymphocytes. This has been

hypothesized to be a CD-8 T-cell mediated phenomenon based on the

infiltration of this cellular subset and expression of major histocompatibility

complex class II antigens.6

Initial surgical

excision usually is curative; however, a second surgical excision may

be necessary for complete cure on rare occasions.1, 6 Due

to the high rate of surgical cure and the probability of spontaneous

regression, few studies have been done addressing alternate forms of

therapy. Infection of ulcerated lesions on the surface of the neoplasm

is probably the primary indication for surgical intervention.

Summary

Cutaneous histiocytomas

are benign round cell tumors of Langerhans cell origin. Neoplasms are

seen predominantly in young dogs, but can occur in older dogs. These

neoplasms usually appear as small, red, raised, sparsely haired

nodules that often have an ulcerated surface. They are observed most

commonly on the head and neck, but may occur on the trunk and limbs,

including the feet and toes. Diagnosis can generally be sufficiently

made on the basis of history, signalment, and fine-needle aspiration

cytology. In some instances, histopathology may be required for a

definitive diagnosis. Most histiocytomas regress spontaneously without

treatment; however, surgical excision is usually curative. These

neoplasms rarely metastasize and the prognosis for non-recurrence is

excellent.

References

1. Affolter VK, Moore P.F. 2000. Canine cutaneous and systemic

histiocytosis: Reactive histiocytosis of dermal dendritic cells. Am J

Dermatopathol 22:40-48.

2. Aiello SE, Mays A (eds). 1998. Tumors with histiocytic

differentiation. Merck Veterinary Manual, 8th ed. Merck & Co.,

Inc, Whitehouse Station, NJ, pp. 708-709.

3. Bonnett BN, Egenvall A, Olson P. 1997. Mortality in insured

Swedish dogs: Rates and causes of death in various breeds. Vet Rec

141:40-44.

4. Dee ONT, Dorn CR, Luis OH. 1969. Morphologic and biologic

characteristics of the canine cutaneous histiocytoma. Cancer Res

29:83-92.

5. Dobson JM, Samuel S, Milstein H, Rogers K, Wood JLN. 2002.

Canine neoplasia in the UK: Estimates of incidence rates from a

population of insured dogs. J Small Animal Pract 43:240-246.

6. Kipar A, Baumgartner W, Kremmer E, Frese K, Weiss E. 1998.

Expression of major histocompatibility complex class II antigen in

neoplastic cells of canine cutaneous histiocytoma. Vet Immunol

Immunopathol. 62:1-13.

7. Michell AR. 1999. Longevity of British breeds of dog and its

relationships with sex, size, cardiovascular variables and disease.

Vet Rec 145:628-629.

8. Moore PF. 1986. Characterization of cytoplasmic lysozyme

immunoreactivity as a histiocytic marker in normal canine tissues. Vet

Pathol 23:763-769.

9. Moore PF, Schrenzel MD, Affolter VK, Olivry T, Naydan D. 1996.

Canine cutaneous histiocytoma is an epidermotropic Langerhans cell

histiocytosis that expresses CD1 and specific beta 2-integrin

molecules. Am J Pathol 148:1699-1707.

10. Peters JH, Gieseler R, Thiele B, Steinbach F. 1996. Dendritic

cells from ontogenetic orphans to myelomonocytic descendants. Immunol

Today 17:273-278.

11. Shortman K, Caux C. 1997 Dendritic cell development: Multiple

pathways to natures adjuvants. Stem Cells 15:409-419.

12. Tizard IR 2000. The organs of the immune system. Vet Immunol

6:69-83.

Canine Cutaneous Histiocytoma

Josh R. Woods, DVM; Kenneth S. Latimer, DVM, PhD; Perry J. Bain DVM, PhD

Class of 2004 (Woods) and Department of Pathology (Latimer, Bain),

College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Georgia, Athens, GA 30602-7388

Web Page